“[Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wasmuth portfolio], Wagner’s Modern Architecture, and Loos’ Ornament and Crime were the main theoretical baggage which Schindler had collected and carried with him when he left for the United States.” (Gebhard 1972 p14)

Arrives in the United States aboard the Kaiserin Auguste Viktoria (Hailey 2008 p224)

Arrives in the United States in New York on March 7, 1914 (de Michelis 2005 p3)

Visits New York for two weeks (Steele 2005 p91)

Schindler on New York: “The endless rows of windows built up against the sky are, close at hand, quite disappointing to the architect because everything is still rough, only calculated for mass effect—no, generated through mass demand." (de Michelis 2005 p3)

Schindler to Richard Neutra in a letter dated March 1914: "Now that I have overcome the confusion of the first fortnight the thousand new movements will become habit. It has been a trip into a new strange life ending in New York—which after the long days on the plane of water rose out of the bottom of the bay as an adventure—the city." (McCoy 1974 p219)

Travels to Chicago (Steele 2005 p91)

Gets a three-year contract to work as an architectural draftsman at Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert (Steele 2005 p91)

Henry Ottenheimer had worked for Adler & Sullivan (Gebhard 1972 p21)

Schindler is disappointed in the work at Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler is disappointed in American architecture, its modernistic tendencies driven more by budget and limited contractor ability than theory (McCoy 1960 p153)

Technologically, architecture in Chicago was on the forefront; stylistically it was not (Gebhard 1972 p22)

Schindler meets Louis Sullivan in spring 1914 (McCoy 1961 p179)

Participates in meetings and exhibitions in the Chicago Architectural Club (Gebhard 1972 p24)

World War I starts in Europe on July 28, 1914.

Schindler sends a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright dated November 23, 1914, introducing himself as a "pupil of Otto Wagner in Vienna" and expressing his eagerness to work with him. Wright responded immediately inviting Schindler to his office to speak with him. (de Michelis 2005 p5)

Schindler's personal notes: ”What we feel to be modern in American architecture is for the American architect the expression of those repulsive forces which he calls ‘contractor and budget’.” (Urbanops 2013)

Schindler aboard the Kaiserin Auguste Viktoria in March 1914

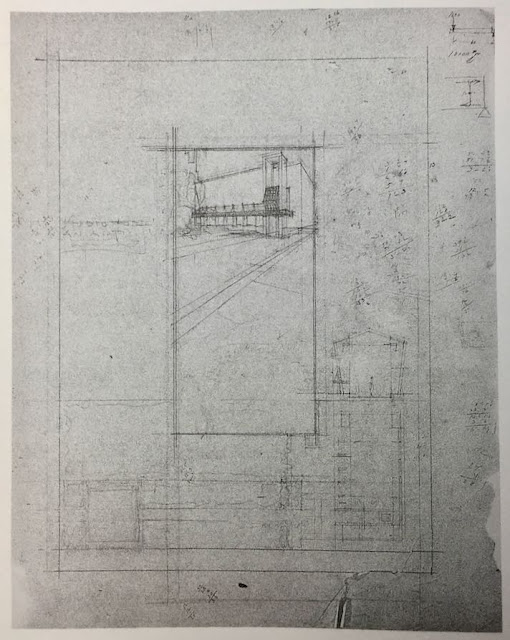

1914: Project for a neighborhood center (Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p24 1993c xvii)

A few months after arriving in Chicago, Schindler enters a design competition held by the Architectural Club for a neighborhood center (Gebhard 1972 p24)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p26)

1915

Late in summer of 1915, Schindler takes a train to New Mexico, Arizona, and California (Gebhard 1972 p27)

Schindler also visited Denver and Salt Lake City (de Michelis 2005 p3)

“...he was deeply affected by the vernacular architecture of the upper Rio Grande Valley.” (Gebhard 1972 p27)

In New Mexico Schindler found "...the first buildings in America which have a real feeling for the ground which carries them." (McCoy 1960 p153)

"The deep impression that Indian pueblo architecture left on him and his unforgettable experiences 'among Indians and cowboys,' which he wrote about to Richard Neutra, can be traced in the numerous photographs and sketches Schindler made during his stay in New Mexico." (de Michelis 2005 p3)

In California he takes note of Irving Gill’s work. (Gebhard 1972 p31)

Schindler in Taos, New Mexico, 1915

photo by R.M Schindler, Taos Pueblo (via McCoy 1979 p76)

photo by R.M Schindler (UC Santa Barbara Art, Architecture and Design Collections, R. M. Schindler Papers)

photo by R.M Schindler

photo by R.M. Schindler?

drawing Schindler made in northern New Mexico, R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p27)

photo by R.M. Schindler of the Panama Pacific Exposition, September 1915, San Francisco (R.M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collection, University of California at Santa Barbara, via Southern California Architectural History)

photo by R.M. Schindler of the Panama Pacific Exposition, September 1915, San Francisco (R.M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collection, University of California at Santa Barbara, via Southern California Architectural History)

photo by R.M. Schindler of the Panama Pacific Exposition, September 1915, San Francisco (R.M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collection, University of California at Santa Barbara, via Southern California Architectural History)

1915: Project for an 11-story hotel (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in (Gebhard 1972 p27+196 Gebhard 1993c xvii)

1915: Project for a bar (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 Gebhard 1993c xvii)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p73)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p30 1993c xvii)

“His scheme for the Martin house shows at an early point in his career his willingness to modify or completely throw off parts of his theoretical baggage if they got in the way of his design process.” (Gebhard 1972 p30)

The hearth has a footprint of 24 feet by 6 feet (March 1995b p113)

"Why have architects not more often seen the earthbound masses of Pueblo architecture as an inspiration for their own work, and, when they have, why is it they have missed the secret that Georgia O'Keeffe, a painter, clearly mastered? ...Mary Colter came close, as did John Gaw Meem at the University of New Mexico. But the best architecture to come from the serious attempt to understand the Native American architecture or its Spanish interpretation significantly never got beyond the drawing boards. It was the projected T.P. Martin house (1915) by R.M. Schindler. There is one drawing of its interior patio in Gebhard's article in Pueblo Style (p. 154), but the really telling one is in his Schindler (p. 28). Perhaps it is best left on paper, especially in Schindler's expressionistic rendering, which is itself a work of art. Even in his finest work he never realized its simple monumentality, though there are many examples of his being influenced by Southwestern forms." (Winter 1992 p332)

"It was R.M. Schindler...who translated the plastic surface effects and the projecting vegas of Pueblo architecture into a highly original form, first in his project for the Martin house at Taos, New Mexico (1915), then in his Pueblo Ribera apartments at La Jolla (I923), and in the concrete walls of his own house in Hollywood (I922)." (Gebhard 1967 p146-7)

published in Tallmadge (1917) and Chicago Architectural Club (1917)

1915-6: Project for the Homer Emunim Temple and School (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Steele (1985) [Giella (1995 p47) shows 1916 as the date]

"..astonishing..." (Giella 1995 p47)

R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p31)

(via McCoy 1979 p75)

1916

"make a circle tour of the West"; attended the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco and the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego (McCoy 1960 p153) [doesn't match with Gebhard (1972) who says Schindler traveled in late 1915 and designed the adobe house for Martin in 1915]

In New Mexico Schindler finds "the first buildings in America which have a real feeling for the ground which carried them" (McCoy 1960 p153)

Lectures at the Chicago School of Applied Art where his prospectus states "He believes that the creative side of architectural work is the most important, and that undue emphasis is placed on historical and technical knowledge." (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler first inquires about working for Wright in 1916 (Gebhard 1972 p37)

photo by R.M. Schindler of Chicago, the Art Institute on the right (R.M. Schindler Collection, Architecture and Design Collection, University Art Museum, University of California at Santa Barbara, via Southern California Architectural History)

photo of Chicago by Schindler (via Steele 1999 p 6)

1916: Drawing at the Art Institute

Schindler gives "a series of twelve elaborately prepared lectures, serving as an introduction to architecture, that he delivered in 1916 at the Church School of Design in Chicago." 112 pages of hand-written notes (de Michelis 2005 p2)

"According to Schindler, a conventional academic education provided the ability to imitate any style, but did not give the student any sense of what architecture really was." (de Michelis 2005 p2)

Starts drawing at the Art Institute (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler’s drawings, at least, were influenced by Klimt, Kokoschka, and Schiele (Gebhard 1972 p13)

About his drawings: “These figures are neither enticing, nor erotic; they are fascinating but slightly repulsive.” (Gebhard 1972 p24)

R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p23)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p25)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p7)

As noted in Steele (2005 p91) and Gebhard (1993c xvii)

R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p35)

1916: Hampden Club (Chicago, Illinois; _______)

"The plastic character of the adobe pueblo was evident in the model he made of the first designs for the Hampden Club in 1916." (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler designed and superintended construction (McCoy 1960 p153)

1916: I Am Temple (with Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; 176 West Washington Street, Chicago, Illinois; still exists)

As noted in Sinkevitch and Petersen (2014 p84)

"...the Temple's unusual character is ascribed to the fact that the Viennese-born Rudolph Schindler was working for this firm." (Sinkevitch and Petersen 2014 p84)

photo by the author (Robert E. Mace) 2014

1916: Project (residence) for J.B. Lee (Maywood, Illinois)

An experiment in prairie style (Gebhard 1972) [same as the remodel?]

1916: Project for a central administration building (with Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert)

As noted in Steele (2005) and Gebhard (1993c xvii)

(Gebhard 1993a)

1916-7: Project for a log house

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p32 1993c xxvii) [Gebhard (1993c) shows 1918]

Designed in 1916 and finished at Taliesen the following year; intended to be a summer vacation house (Gebhard 1972 p32)

The thin bands of windows at the top reappear in Pueblo Ribera Court (Gebhard 1972 p34)

The design uses a horizontal and vertical four-foot module, something Schindler used, with minor refinements, in most of his later work (Gebhard 1972 p34)

An experiment in Prairie style (Gebhard 1972)

The plan is dated 'Taliesin, April 1918' (March 1995b p103)

Schindler may have seen Adolf Loos' log house for the janitor of the Schwarzwald School (March 1995b p103)

'The roof of the Log House is flat. For its time this is noteworthy." (March 1995b p106)

'[The clerestory band] is not characteristic of Wright's domestic work up to this time..." (March 1995b p108)

Schindler uses clerestories in the Kings Road House in 1921-2. Wright introduces clerestories into his work with the Freeman House in 1924. (March 1995b p113)

Mark Schindler makes reference to Karnak concerning the inspiration for Schindler's clerestories; however, this cannot be confirmed (March 1995b p108)

1916: Project (new storefront) for Van Buren Street (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p31+196 1993c xvii)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p31+196 1993c xvii)

photo by Julius Schulman 1982 Getty Research Institute

An experiment in prairie style (Gebhard 1972 1993c xvii)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p36)

1916-8: Buena Shore Club House (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois; demolished)

As noted in Steele (2005 p91) and Gebhard (1972 1993c xvii) [Gebard (1972) lists dates as 1917-8 (and also as 1917) while Steele (2005) and Giella (1995 p39) lists dates as 1916-8] and Smith and Darling (2001 p228; lists 1916-8)

Also called the Hampden Club: the Buena Shore Club was an outgrowth of the Hampden Club (Giella 1995 p39)

Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert, among other firms, were invited to submit plans for the club (Giella 1995 p39)

Schindler: "I criticised the architects and scheme in the office and was told 'to do better'. I did. My plans were entered into the competition by my employer, together with the official scheme, and finally accepted by the owner for execution." (Giella 1995 p39)

First model reflected influence of the plasticity of adobe architecture (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler designed and superintended construction (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler: "I was superintending the Elks Club at the time and the office proceeded with my sketches as a basis. It was too much for them—the building having been conceived in three dimensions instead of the usual two. The working plans proved to be an absolute chaos and the contractor threatened to quit the work. Only then was I asked to [take ahold] of the superintending... In this way I was able to save something of the general idea of the building, but was unable to develop the details covered by the contracts and defined by the foundations already in place. The building is a bastard." (Giella 1995 p39)

"Building pays tribute to his beloved teacher Otto Wagner as well as Louis Sullivan." (McCoy 1954 p12)

Featured built-in furniture (McCoy 1960 p153)

Schindler designed the light fixtures (Giella 1995 p43)

Schindler left Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert on November 1, 1917, to complete the building in the employ of the club through January 1, 1918 (Giella 1995 p39)

"...the only building both designed and executed by Schindler in Chicago..." (Giella 1995 p39)

"...the largest and most complex building in his oeuvre..." (Giella 1995 p39)

"The internal spatial complexity is so staggering that it almost defies description..." (Giella 1995 p43)

"According to his wife, Pauline Gibling Schindler, the architect himself considered this his first opus." (Giella 1995 p39)

"...the Buena Shore Club deserves to be considered one of the most advanced buildings in Europe and America of its day." (Giella 1995 p47)

Schindler: "This is the house—this is how the Architect has seen it and is trying to describe it. He knows his words are futile—go, see the house and enter it—breathe its air and touch its [walls]..." (Giella 1995 p41)

published in The Western Architect (1916)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p38)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p38)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p38)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p39)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p18)

from the Ester McCoy archives at the Smithsonian

from The Western Architect (1916)

from the Ester McCoy archives at the Smithsonian

from the Ester McCoy archives at the Smithsonian

photo by R.M. Schindler, R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p22)

photo by R.M. Schindler, R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p33)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p43)

(via March and Sheine 1995 p47)

1917

(via Gebhard and others 1997)

photo used to advertise grand opening of the Buena Shore Club (via March and Scheine 1995 p48)

"He did not go to Wright as an apprentice..." (McCoy 1953 p12)

"For all intents and purposes, from 1917 to 1921, [Schindler] was Wright's partner in all but name." (Park and March 2002 p478)

His first job for Wright was to revise the engineering on the Imperial Hotel (McCoy 1953 p12)

Schindler’s engineering background was valuable in completing working drawings for the Imperial Hotel, especially its foundation (Gebhard 1972 p37)

Schindler started work with Wright without a salary; he worked on the side to make ends meet (McCoy 1960 p154)

“[Wright] must have had some respect for his abilities, for otherwise he would not have given [Schindler] the responsibility for the completion of several designs and the supervision of such an important commission as the Hollyhock House.” (Gebhard 1972 p37)

Lists Schindler's address as 220 South State Street in the catalog for the 30th Annual Chicago Architectural Exhibit (unclear if place of business or residence; address doesn't exist today):

220 South State Street? Note the Mies van der Rohe' lurking behind...

as shown in Tallmadge (1917)

United States formally enters World War I on April 6, 1917.

1917: Project for Melrose Public Park (Melrose, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii)

1917: Project for a three-room house (Oak Park, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii)

1918

Wright moves his office to Taliesen on February 15, 1918 (McCoy 1960 p154)

Taliesen, photo by R.M. Schindler (via McCoy 1979 p77)

Taliesin 1918, photo by R.M. Schindler (via McCoy 1974 p221)

Taliesen. From left: William E. Smith, R.M. Schindler, Arato Endo, Goichi Fujikura, and Julius Floto (via Southern California Architectural History)

1918: Henhouse for Taliesen (Spring Green, Wisconsin)

As noted in Gebhard (1997 p. 175)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p175)

1918: Project for a children's corner for the Chicago Art Institute (Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii)

R. M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara

1919

Meets Pauline Gibling at a Sergei Prokofiev concert (Warren 2011 p251)

Meets Pauline at a performance of Prokofiev's Scythian Suite. "Greatly aroused, they 'couldn't stay for the von Weber.'" They were married three months later. (Sweeney and Scheine 2012 p12)

Pauline had studied at Smith College and was a music teacher at Jane Addams' Hull House (Scheine 1998 p231)

Marries Sophie Pauline Gibling in Evanston, Illinois (Steele 2005 p91)

Schindler and Gibling marry in August (Warren 2011 p251)

Marry on August 29th (Sweeney and Scheine 2012 p12)

In August, the Communist Labor Party was created in Chicago. Pauline to her parents: "We are Communists!" (Sweeney and Scheine 2012 p12-3)

The Schindlers lived for a time in Wright's Oak Park house (Sweeney and Scheine 2012 p13)

"Schindler...essentially ran the Wright office from 1919 to 1922..." (Scheine 1998 p15)

Schindler: “Not one of Wright’s men has yet found a word to say for himself.” (Gebhard 1972 p45)

Wright in a letter to Schindler: "Regarding prospective clients - 'Schindler' is keeping my office and my work for me in my absence. He has no identity as 'Schindler' with clients who want 'Wright.'... I really do not know quite what a 'Schindler' would look like. You know much better what 'a Wright' would look and be like and as the clients came to get it. The natural thing would be it would seem to lay it out as nearly as you can as I would do it and send it here for straightening... Nicht wahr?" (de Michelsi 2005 p5)

Schindler works to try and get Sullivan's Kindergarten Chats published in Austria via Adolf Loos (McCoy 1961 p179)

Pauline (Gibling) Schindler

1919: Memorial Community Center Garden (for Frank Lloyd Wright; Wenatchee, Washington; ________)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii) and Steele (2005 p91)

1919: Project (residence) for J.P. Shampay (for Frank Lloyd Wright; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii), Steele (2005 p91), and Park and March (2002 p473) [Park and March note the location as 'Beverly Hills']

"...the very last of Frank Lloyd Wright's cruciform Prairie houses." (Park and March 2002 p470)

"Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer...regards the house as a direct source for the development of Wright's Usonian houses..." (Park and March 2002 p470)

"Pfeiffer also appreciates the transitional quality of the project among Wright's work, especially in the way the living areas are opened up to the garden." (Park and March 2002 p470)

Henry-Russel Hitchcock recognized in 1972 (Hitchcock 1972) that the Shampay House had been designed by Schindler (Park and March 2002 p470)

Wright to Schindler in a letter dated May 27, 1919: "The Shampay—(I hope he won't be shamming when it comes to paying) plan arrived and has a familiar look—. the 'per Schindler' rather silly, nicht wahr? However Schindler must live and ought to if this helps him to do so—all right. The plan is rather complex as to 'fi...t' [unreadable] the general ground plan arrangement seems good. Keep it all simple. I am sensible of over elaboration of my scheme of articulation in the hands of others and in my own hands too—It is a fascinating vice in extremes and hard on an owner—So be careful__" (Park and March 2002 p472)

"The Shampay House derives not from a radical break with the Prairie tradition, but rather from a masterful distillation and amalgamation of a range of pre-existing tendencies present in Wright's practice." (Park and March 2002 p474)

"...there is little indication that Schindler took note of Wright's suggestions. None of Wright's comments on the blueprints seem to have inspired or even influenced the development of the design." (Park and March 2002 p474)

(as shown in Park and March 2002 p473)

Floorplan as shown in Scheine (1998 p53)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p196 1993c xvii) and Steele (2005 p91)

1919: Project (studio for an artist) for Rudolph Weinsenborn

As noted in Gebhard (1993c p xvii)

(from Gebhard 1993d)

1919: Project for one-room apartments (for Ottenheimer, Stern, and Reichert; Chicago, Illinois)

As noted in Gebhard (1972 p197 1993c xvii)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1997 p18)

As noted in Gebhard (1993c xvii)

Henry-Russell Hitchcock pointed out that one of Wright’s most significant works in the 1910s was the project for a Workman’s Colony of Concrete Monolith Homes. The Monoliths anticipated Wright’s precast concrete block homes of the 1920s. Gebhard notes that the “stark stripped-down rectangularity of the geometry, in the details as a well as in the relationship of the volumes, could have been Schindler’s contribution.” (Gebhard 1971 p39) [It was later confirmed that Schindler designed the project.]

The monoliths anticipated Pueblo Ribera (Gebhard 1972 p39)

R.M. Schindler papers, Architecture & Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara (via Gebhard 1972 p38)

1919: Unidentified hotel lobby window

As noted in Gebhard (1993c p xvii)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment